“Songs for Drella”, an intimate homage to the deceased Andy Warhol composed by Lou Reed and John Cale, was the initial spark which prompted the painter, Marie Pittroff, to express her intensive but unsentimental relationship to Lou Reed as an artist. If music and text can portray a painter, why not the other way round? Why should a painter not portray a singer and poet, a person of her own generation?

The paintings of Lou Reed by Marie Pittroff do not wear with time, any more than the music of Lou Reed – they have a timeless dimension. Nevertheless, we will undertake a short journey through time: to Andy Warhol, Lou Reed, The Velvet Underground and to the “avant-garde consciousness” they advocated in those days – but, in fact, what Andy Warhol did and what The Velvet Underground sang received little recognition at first.

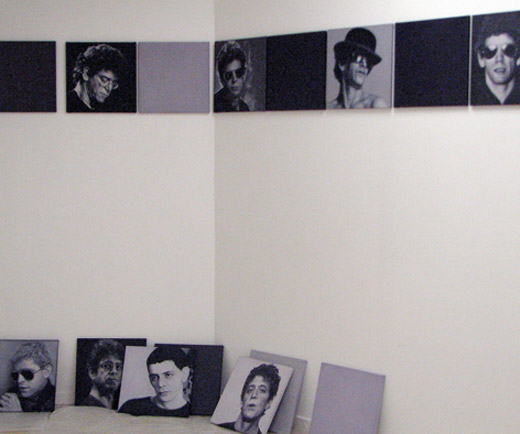

Marie Pittroff : LURID – Hommage to Lou Reed (in the Galerie Suty)

Let’s look back at the “Zeitgeist” (spirit of the time) in the mid-sixties: life on the razor’s edge; everything is possible – BE YOUR OWN LAW – don’t stand still: the whole range of human emotions in totality seems legitimate and realizable, an exciting and energized time of artistic networks. POP MEANS THAT ANYBODY CAN DO ANYTHING AND TRY OUT ANYTHING. Nobody has to put up a front; everything can become reality. The wish to do something special is no longer taboo – art touches the context of rock music – stimulations, reflections, magnetic attractions.

And in the midst of all this, in the middle of New York City, the city Lou Reed once referred to as “his DNA”, was Andy Warhol’s “Factory“, at that time called “The Silver Factory”, completely covered by silver foil or sprayed with silver paint, even the windows – always night, an atmosphere of neon lights. A nest for speed freaks, outsiders, drag-queens, unknown artists: all dropouts. It was also logically a magnet for the money-aristocracy with tendencies toward decadence – they mingled and took photographs, filmed and danced, while Warhol worked and worked. Broken mirrors, the speed freaks’ symbol, hung on the factory walls – I see myself as a broken form. Next to the only telephone was a broken mirror so a person could see his reflection during trivial phone conversations: a highly dynamic, creative and explosive interweaving – sometimes authentic, sometimes stylised.

The Velvet Underground was Andy Warhol’s latest showpiece, but it had a life of its own: a fusion of John Cale’s background of classical and FLUXUS avant-garde music and Lou Reed’s aggressive rock ‘n’ roll with sharp-edged poetry; above all, the song texts – finally no more “peace-joy-I-love-you-texts” but adult texts with controversial topics, songs about things happening around them; texts about death, pain, suffering, perversion; honest texts, gloomy but expressing tenderness and commitment; outsider songs and love songs – all topics, SIMPLY EVERYTHING – songs of literary standards, confrontational, unnerving, realistic. “You aren’t writing for a majority when you write about things that hurt,” said Lou Reed. Accordingly, The Velvet Underground was attacked and criticized, but they remained unwavering and did their thing, just like the “mastermind”, Andy Warhol – NOBODY IS SPECIAL OR EVERYBODY IS.

The merging of literary art and trash, sensitivity and coarseness, tenderness and violence; journeys through the urban underworld; pale skin, black leather, inner conflict, uncertainty and despair – that was the anti-alternative culture – hyperactivity, feverish energy, rage against life, dancing on a volcano. The present is wonderful, open, free, fruitful; one tackles the moment while chaos reigns and, contrary to the hopes of the hippies, knowing that things will not stay the way they are.

The music of The Velvet Underground is revolutionary, discordant, eruptive, full of screeching feedback. The texts describe damaged relationships rather than all-embracing love. The spontaneous, improvised music of the hippies collides with the ironic tension, the stylised and intellectual form of The Velvet Underground – which can even be physically perceived. The pale and reticent metropolitan individual hiding behind sunglasses stands in contrast to the tanned, laid-back, friendly hippy whose optimistic world view is negated by the urban person who can no longer ignore the violence, filth, crime, suffering. Still, we must not forget that what The Velvet Underground made out of all this was a product of art – the result of a creative process, with detachment and self-irony.

At this point let us return to the work of Lou Reed and Marie Pittroff. Lou Reed is a bohemian, a romantic and, at the same time, an anti-romantic: paranoia and love are in competition. He writes obsessively about reality, acts out his changing moods in an urban hell, avoids being pinned down to a particular role or manner of behaviour. He reflects his fears, the depths of his soul, his vulnerabilities, and his generation’s self-assertion and defiance. As in the work of Lou Reed, we can see in Marie Pittroff’s paintings a basic scepticism towards general truths and utopian dreams.

Just as Reed uses a concise, unpretentious and direct style of language, so also does Pittroff work with a minimal palette of colours. Pittroff’s city-paintings evoke basic human loneliness and urban isolation: they show modern artefacts behind the veil of maya, in a world which seems unreal and difficult to relate to. The viewers of the pictures are dependant on their own personal associations and memories. The world as such cannot be grasped by human perception, no clear interpretation is possible, everything remains uncertain. Pittroff’s detached view through the veil causes disturbance – the borders of reality become perceptible but cannot be crossed, no cosy place is to be found, only the longing for it remains.

Marie Pittroff selects pictures from newspapers and magazines or snapshots and photos taken by herself or friends and she gives them new meaning. She consciously chooses the layer technique of oil painting for its seductive and sensual surface. She uses the classically distinctive quality of traditional oil painting to create an “auratic” – perhaps erratic – work: remote yet inviting and, above all, original. Distinct from its model, a unique work is made, something singular – in contrast to the medium of mass-produced copies. Pittroff plays at creating photo-realistic pictures using monochrome reduction. The work resulting from this time-consuming procedure of painting in layers is a lasting value, time lived by the artist.

Taken together, the paintings are conceived as a series. However, they also serve as independent pictures. The picture installation of Lou Reed portraits is intentionally not arranged chronologically – such a linear impression is cancelled by the side-by-side images which show simultaneously the facets, ego-fragmentations and contradictions of Lou Reed – and maybe also of Marie Pittroff and a whole generation.

Marina Stauffer 2002 (Südwestrundfunk), Translation: Joan Duchesne